Many speakers we work with want to use quotes in their speeches. Others wonder whether they should—as if it's expected.

So we found a lot to love in the recent news story about a high school valedictorian who claimed he was quoting Donald Trump, got huge cheers, then revealed the true source was Barack Obama.

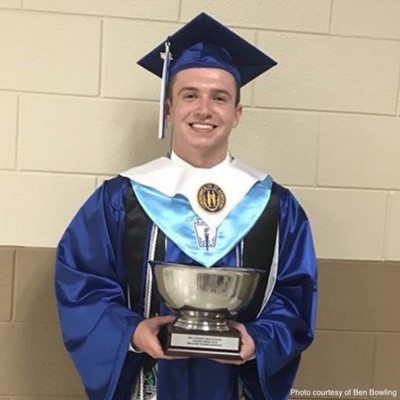

That story delivers a mini-lesson in using quotes in speeches. Here’s what you can learn from Ben Bowling’s speech, plus a few of our observations from years of presentation development, speechwriting, coaching, and teaching.

Quotation, n: The act of repeating erroneously the words of another.

– Ambrose Bierce

It’s not exactly original to use a quote.

It’s one of the first things people think of, right up there with giving the dictionary definition of a key word in their speech.

Ask yourself if the quote is the best tool for the job.

If your first instinct is to use a quote (see above), ask yourself if this is the best way to get your message across. Why are you using it? Does the quote bring something to your speech or presentation that your own words can’t?

Ben Bowling making headlines for his deft use of a quote in his graduation speech, June 2018

Ben Bowling making headlines for his deft use of a quote in his graduation speech, June 2018

It’s great if the quote can add humor or bring an unexpected twist.

Take a look at Bowling’s speech, for example. He uses a quote that’s pretty typical for a graduation speech: "Don't just get involved. Fight for your seat at the table. Better yet, fight for a seat at the head of the table." But he knew his audience and he brought a twist, attributing that quote at first to Donald Trump, then revealing those to be the words of Barack Obama.

"Y'all, no lie—the valedictorian just quoted Trump and everyone cheered ... then he told us that it was actually an Obama quote. Best part of the day. I'm rolling," tweeted audience member Alisha Russell.

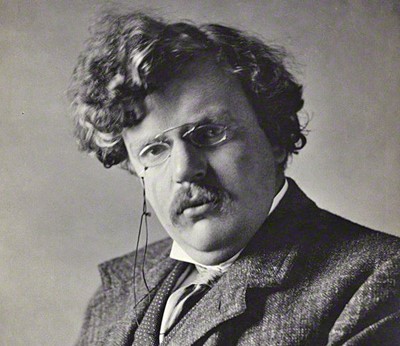

Buckley faculty Jenny Maxwell regularly uses this quote from G.K Chesterton when she teaches about the value of using concrete language instead of broad, generic words:

"The word ‘good’ has many meanings. For example, if a man were to shoot his grandmother at a range of five hundred yards, I should call him a good shot, but not necessarily a good man."

The quote illustrates her point and gets lots of laughs every time.

G.K. Chesterton

G.K. Chesterton

If the person you’re quoting isn’t recognizable to your audience, you may have a problem.

If you’re quoting Aristotle or Oprah, you can probably expect that the source of your quote will bring some authority. (Though that can have its problems, too. Christopher Buckley tells a funny story about speechwriting for George H.W. Bush. He quoted Thucydides, a name Bush struggled to pronounce. “Next time, make it Plato,” Bush supposedly told him.)

What if you’re quoting someone who is less well-known? We most commonly see that happen when speakers want to quote business self-help authors whose names are not exactly household words.

Our general guide—if you have to do a lot of explaining to set your source up as a notable source, reconsider. Are their words worth the effort? Does the payoff justify the setup?

Jenny admits she worried that the majority of people in her classes wouldn’t know G.K. Chesterton, though it turns out it doesn’t matter. She just sets it up by referencing him as “the British writer” and the point made so humorously by the quote takes care of the rest.

Know the context of the quote.

In his valedictory speech, here’s how Ben Bowling leads into the quote that made headlines for him:

"This is the part of my speech where I share some inspirational quotes I found on Google."

Truer words have rarely been spoken. How many of us haven’t Googled to find a quote for a presentation?

The risk in that is one our founder used to caution against. Reid Buckley felt you should have read the material you were quoting, so that you’d understand the context around the line you’d extracted. Otherwise, he said, you risk having someone in the audience call you out.

It can happen, despite the observation of Bowling’s high school principal, Richard Gambrel, who told The New York Times that the audience response to the quote in the speech “proves that people don’t read or pay attention.”

"There's a sucker born every minute."

– P.T. Barnum or some other guy

For heaven’s sake, get it right.

Another pitfall of the Google-and-quote approach is that you’re likely to find some fake quotes out there.

"I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." That’s Voltaire’s most famous quote, but he never said it. Voltaire biographer Evelyn Beatrice Hall wrote those words 100 years later, to illustrate Voltaire's outlook.

Nor did P.T. Barnum give us "There’s a sucker born every minute." Apparently, a frustrated competitor was the source for that one.

If you’re quoting someone in a speech, be sure the audience knows where the quote ends and your words begin.

This is a common frustration for listeners, particularly if the speaker is quoting someone else at length and/or not using PowerPoint to show the quote.

First, we’d suggest you consider shortening the quote. If that’s not an option, you can do the old “quote-end quote” to clue them in.

We’ve also seen it work well to have the quote on a card or piece of paper that you lift up to read—signaling to the audience that you are quoting. You put the paper down at the end of the quote, and they know you’re finished.